Hey, I’ve moved! If you enjoy this post you can find more of my writing at Foreign Exchanges, a Substack newsletter covering a variety of topics in history and foreign affairs. Check it out today and become a subscriber!

One of the things that makes it challenging to study the Mongols is that their empire was so vast and yet so ephemeral that its history was subsumed into several different traditions. For example, if you want to read Mongolian primary sources you need to be able to read not Mongolian (though that helps), but Persian and Chinese, since those were the two languages in which most Mongolian sources were produced. Hardly anybody has ever managed to learn both of those languages well enough to conduct scholarly research in both, and as far as I know none of them has ever bothered producing the definitive work on the Mongol Empire, from one end to the other. Since the history we talk about here deals mostly with the Islamic world, when we encounter the Mongols it’s during their conquests in the Middle East and, occasionally, Europe. I’m afraid Chinese history just isn’t my area.

But I’ve made an exception for 1232-1233 Siege of Kaifeng, because it gives us a chance to talk about some of the military advances that were happening in China at this time and that later impacted the rest of Eurasia and beyond. The Jin dynasty, which ruled northern China at the time, were using early gunpowder weapons. The Mongols may have been using them as well by this point, but the evidence isn’t clear. Some of these devices appear to have been quite devastating, while others were probably meant to frighten an enemy though their actual lethality wasn’t all that great. One of them, the “fire-lance,” had actually been in use in China for a couple of centuries by this point. They all played a role in the Jins’ ultimately unsuccessful defense of Kaifeng against this Mongolian siege. What makes this siege important is not that it’s the first time such weapons were used, but that their use is particularly well-attested at Kaifeng, thanks to a surviving account by a Jin official who lived through the siege.

The Jin Dynasty ruled northern China (which doesn’t exactly correspond with “northern China” as we’d think of it today, but close enough) from the early 12th century until the Mongols toppled them in 1234, a year after Kaifeng. They began as a Manchurian tribe that worked with the southern Song Dynasty to do away with the Liao, who had previously controlled most of northern China. One of the main preoccupations for whichever dynasty controlled northern China at this time was coping with raiding nomadic steppe tribes to the north. The Jin extracted tribute from the tribes, regularly intervened in inter-tribal politics in order to keep any one tribe from becoming too powerful, and at their most fanciful they actually claimed sovereignty over all the tribes. Never let it be said that 12th century Chinese royals lacked a sense of humor.

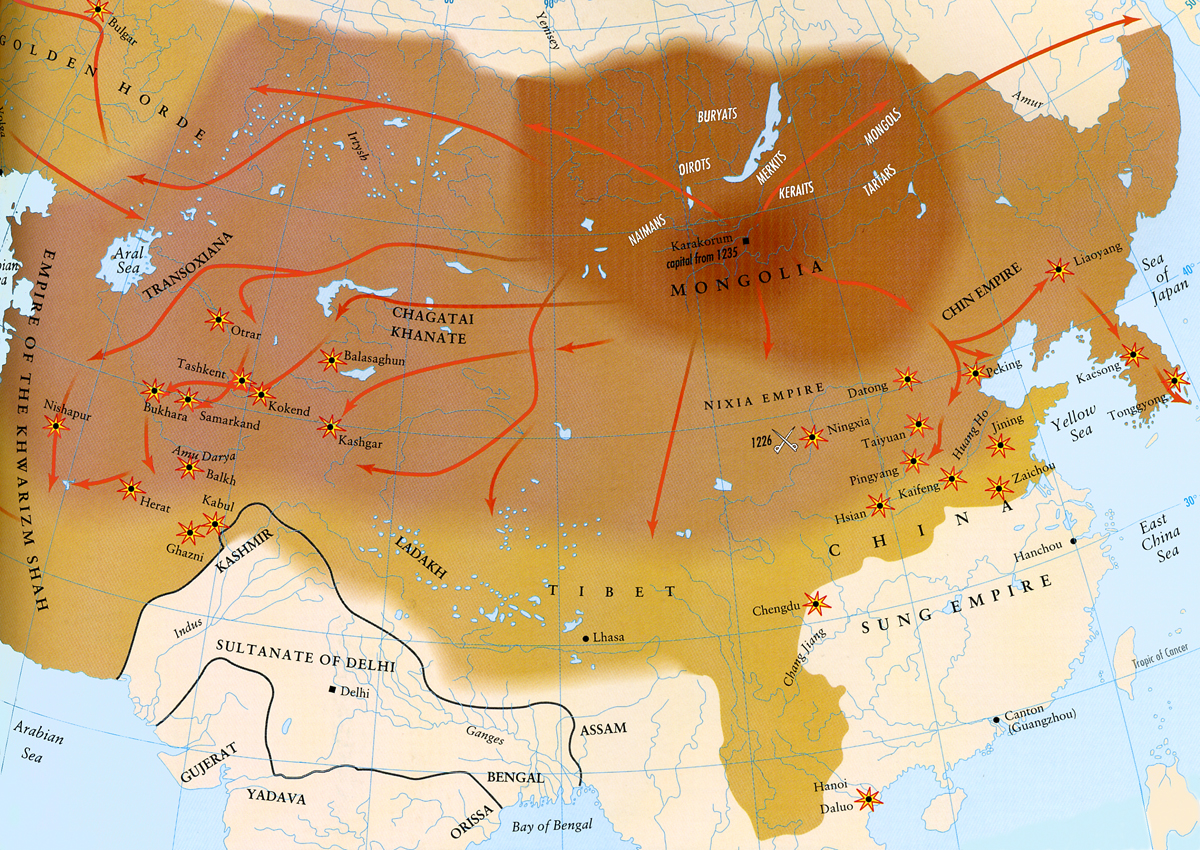

When Temujin (the future Genghis Khan) began his career as a world conqueror, his first order of business was to subjugate all those nomadic tribes under his own banner. For part of this time he actually served as a vassal of the Jin, or more accurately as a vassal of a vassal of the Jin, but he then defeated his former lord and consolidated his own rule over the tribes in 1206, when he officially became “Genghis Khan.” His attention then turned south toward China. His first move was to force Xi Xia (see the map above), ruled by the Tanguts, to submit to his rule, at which point the combined Mongol-Tangut army invaded Jin. In 1215 Genghis Khan besieged and captured the Jin capital, Zhongdu (modern Beijing), forcing the Jin to move their court to Kaifeng. At this point, after 10 years of continuous heavy warfare, the Mongols took a pause. Genghis Khan sent a small force west to conquer the Qara Khitai, the kingdom that had formed in western Liao territory, with the intention of resuming his campaign against the Jin shortly.

The Jin got a few years’ reprieve due to the stupidity of the Central Asian Khwarazmian ruler Muhammad II (d. 1220). In 1219, Genghis Khan, who doesn’t seem to have had any interest–at least at that point–in military activity beyond the former Qara Khitai territory, sent a caravan to the Khwarazmian city of Otrar, with what seems to have been mostly commercial intentions. The governor of Otrar inexplicably (at least in hindsight) massacred the caravan. Genghis Khan then sent diplomatic envoys to Muhammad. Muhammad had them shaved bald, had one of them beheaded, and sent the rest back home in disgrace. Subtlety was not his thing, apparently.

To say that these acts enraged Genghis Khan would be an understatement. To say that they were mistakes on the part of the Khwarazmians would be a much greater understatement. The Mongols invaded and, within two years, utterly destroyed the Khwarazmian Empire. At the end of that adventure, a Mongolian army was sent to ride around the Caspian Sea on an extended raid/scouting expedition. When they returned to Mongolia in the mid-1220s it was time again to focus fully on China. But the immediate problem for Genghis Khan in China was once more the Tangut, who had revolted while he was off defeating the Khwarazmians. It didn’t take very long to reconquer the Tangut, but not long after, in 1227, Genghis Khan died.

Although Genghis Khan had already designated his third son, Ögedei, as his heir, the traditions of a steppe succession process were extensive and these further delayed a new Mongolian offensive against the Jin. But by 1230, the Mongols were able to once again invade Jin territory in force. An army under the legendary Mongolian general Subutai surrounded and laid siege to Kaifeng in early April, 1232. Now, despite rapidly dwindling supplies and the onset of some kind of plague inside Kaifeng, the Jin defenders were able to hold out against the Mongol siege for over 10 months, and this is where, in part, these gunpowder weapons come in.

The most devastating weapons the Jin used were simple gunpowder bombs, which had fuses that were lit on fire before they were launched by trebuchet at the attackers. They exploded on impact, dealing shrapnel damage, and also caught the surrounding area on fire. The Mongol trebuchets could launch massive stones at the city walls, but nothing as devastating to human beings as these gunpowder devices. So the Mongols adjusted. We’re told that they dug approach trenches to get to the city walls and covered them with cowhide shields to protect against shrapnel. The Jin, in response, began to lower their explosives into the trenches on the end of long chains; the effect of their explosions inside the trenches was apparently quite devastating–according to the Jin official who left us an account of the siege, translated by military historian Stephen Turnbull, “the attackers were all blown to bits.”

The other weapon the Jin used were those fire-lances I mentioned above. These were some of the first firearms in history. Probably invented in the 10th century and brought into heavy use by the Song Dynasty, they consisted of a spear with a long bamboo tube tied to it. The tube was packed with gunpowder and tiny projectiles. A soldier would light a fuse, which would ignite the gunpowder and send the projectiles and fire shooting out of the tube. These were of questionable effectiveness–they were almost certainly less lethal than a simple bow and arrow–but the effect of a mass of these things firing simultaneously was probably pretty terrifying to an enemy who hadn’t seen one before. And maybe even to one who had seem them before.

Despite the Jins’ technological superiority, the Mongol siege held, and things inside Kaifeng began to get desperate. On February 26, 1233, Emperor Aizong of Jin (d. 1234) took a chance and fled the city, eventually winding up at Caizhou in August. With the emperor gone, the city’s defenders gave up and let the Mongols in. The emperor died in Caizhou in February 1234, preferring to commit suicide in the face of attacks by both the Mongols from the north and the Song from the south. The Mongols and Song briefly went to war with each other after Jin fell, but the real Mongolian invasion (and conquest, of course) of Song China didn’t happen until the 1250s.